Frankly, I’m surprised at the near-universal praise for Whim W’Him artistic director Olivier Wevers‘ newest work, I don’t remember a spark. Not because I don’t agree with critical and viewer accolades. I do. But because a piece in which an artist opens himself to an audience and talks about what moves him and informs his work is such an obvious target for snarkiness, argumentation or plain distrust of motives. Instead, adjectives like “beautifully dreamed and creatively executed,” “courageous,” “compelling” poured out. Michael van Baker wrote in The SunBreak, “It’s full of wry humor and deprecating touches, but undeniably also suffused with sadness and dislocation.”

Spark, the last of the four pieces on May’s Third Degree program, was performed by five dancers (Tory Peil, Andrew Bartee, Mia Monteabaro, Lara Seefeldt and Sergey Kheylik) against a background of Olivier’s voice incorporated into music by Brian Lawlor.

As Michael Upchurch commented in the Seattle Times, “‘Spark’ neatly sidesteps being a navel-gazing exercise, thanks to the Wevers/Lawlor score which works atmospherically as music (both its sound effects and its actual musical notes) even as it’s filled with Wevers’ disclosures about ‘creative process, insecurities, wishes, pet peeves.‘”

Rachel Gallaher in City Arts found the choreography “gorgeous—effortless lifts, strong group work, a weightless moment when Peil is dragged around the stage on demi-pointe. Despite the specific theme, Wevers has returned to a more original ‘Whim W’Him’ look. He is not trying to follow a storyline, or make the choreography fit into predetermined lines—it is him at his barest, his using the dance as a lens into his life—and that is when he is at his most brilliant.” The nearest thing to a reservation was expressed in Anna Waller‘s for the most part highly positive review for Seattle Dances: “The text was interesting, but sometimes overpowered the dancing, partially because it was so loud against the music. The elements of dance, text, and music did not fully work in concert with one another yet. Furthermore, a work that deals so overtly with artistic process risks toeing the line of pretension. Spark managed to remain on the other side, but only just. It would be fascinating to see it after another round of editing.”

Despite the many hours I have spent watching Olivier work and listening to him talk about dance, I was quite astounded at how elegantly and honestly he dealt with complex, contradictory and very personal themes in this new piece. Olivier’s quintessential characteristics—his passion, training and experience in dance; his well-honed instinct for collaborating with dancers, costumers, lighting and set designers in creating a desired theatrical impact; his self-deprecation (though not self-contempt) and his humor—all fuel and are transformed by a singular choreographic gift.

Instead of leaving the impression of having spilled his own private guts on the floor for his viewers to clean up, Olivier disarms with matter-of-fact candor. “Of course,” says the text in his voice that is integrated into Brian’s score, “I’m totally insecure. I had no idea what it’s going to look like. I didn’t know if it was going to be good or not. I didn’t know if it was going to work. I had to believe that that’s the process that I had to go through.” Yet he somehow does know what good artists do know: how to take the particulars of raw, unattenuated personal experience and convert them, via the tools of his chosen art, into something that touches people, makes them smile, wince, or sigh.

“The more tools you have,” the voice-over remarks, “the more prepared you are.” Nevertheless, it’s a tricky business to pull off, to end up with art and not mere artifice,

to use metaphors without overdoing them, and to admit, as Olivier does at a particularly poignant and candid moment in the text, that “I’m putting myself out there but not really being out there. People are not really looking at me. They’re looking at an image of me, and that’s the image that I want them to see.”

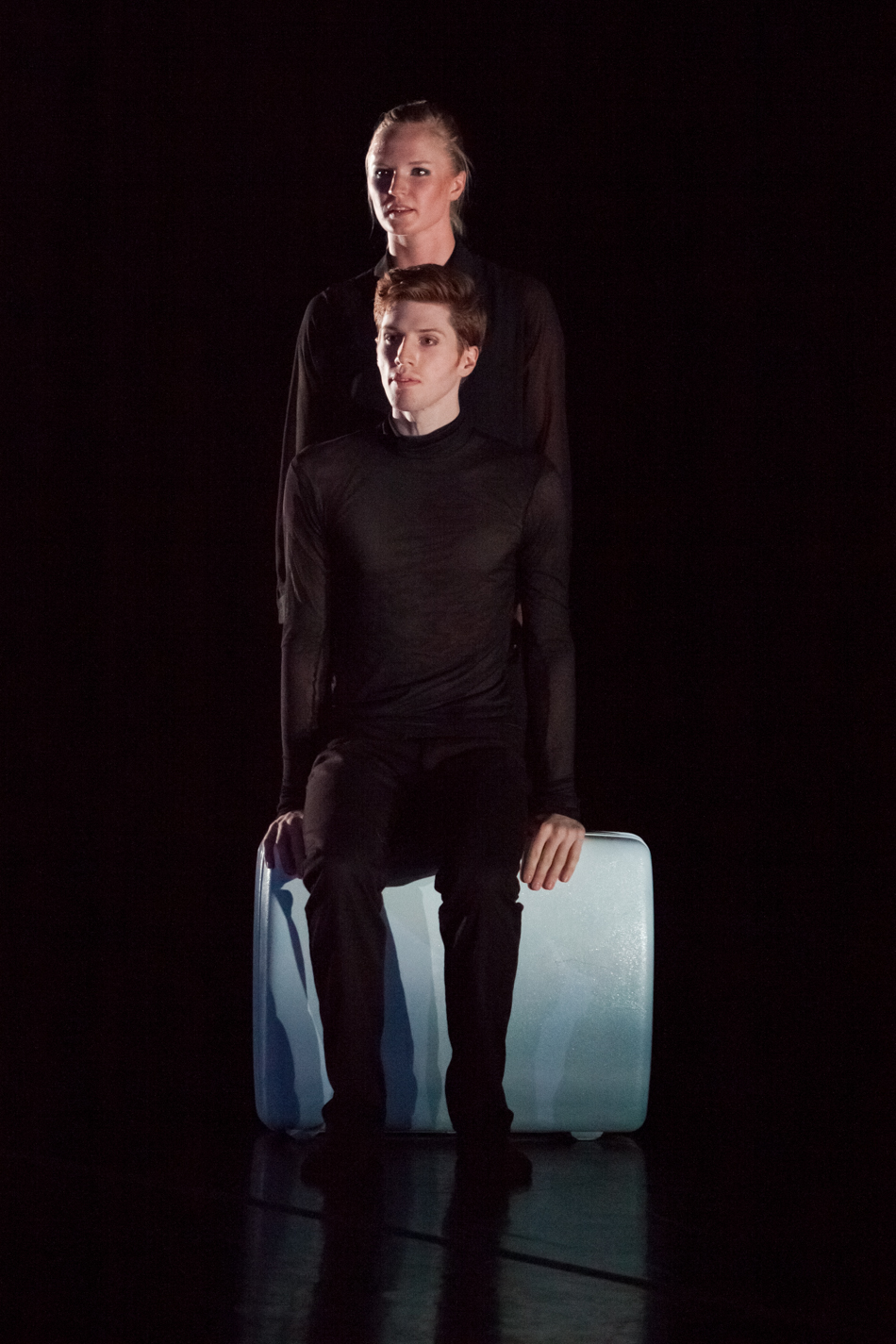

And he makes a great deal of the centrality of the dancers’ marvelous abilities, through a long list of descriptive nouns ending in trust. The dancers “are also judging you,” he says, “And they’re not fully trusting you until they really trust… We have to trust each other.”

In responding to the unheard and unnamed interviewer in the text, Olivier speaks directly, but the dance itself is indirect, open to interpretation. There is a recognition that this is a different art, a different experience than putting things into words. There are amusing visual puns, as when the voice-over says, “I know the mood that I want it to be – what to portray – and then I figure out how to make it fit on my music. Look up at the sky…it’s like finding shapes in the clouds“…

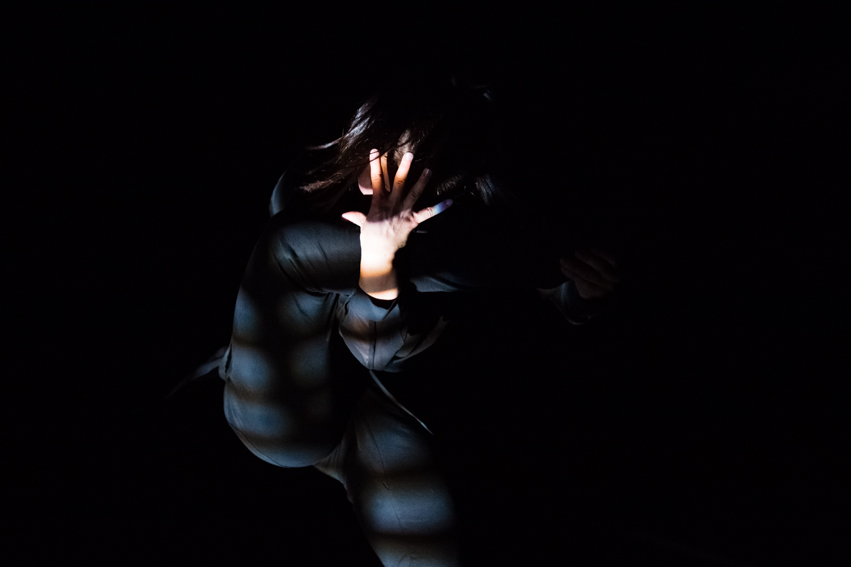

…and correspondences here and there, where something spoken is illustrated by images onstage, as in the section that accompanies the words “There’s moments when you get to the dark side of things. Being angry, jealous, frustrated. Those are the things that you can work on. You also have to accept that is part of being human. It’s part of us. The monster is part of us“…

…or a jittery little teasing of Olivier’s own tendency to preface sentences in rehearsal with “Um” and “You know.”

But there is never just one “meaning” which it is the audience’s job to decipher.

An audience member commenting to the Times review wrote: “

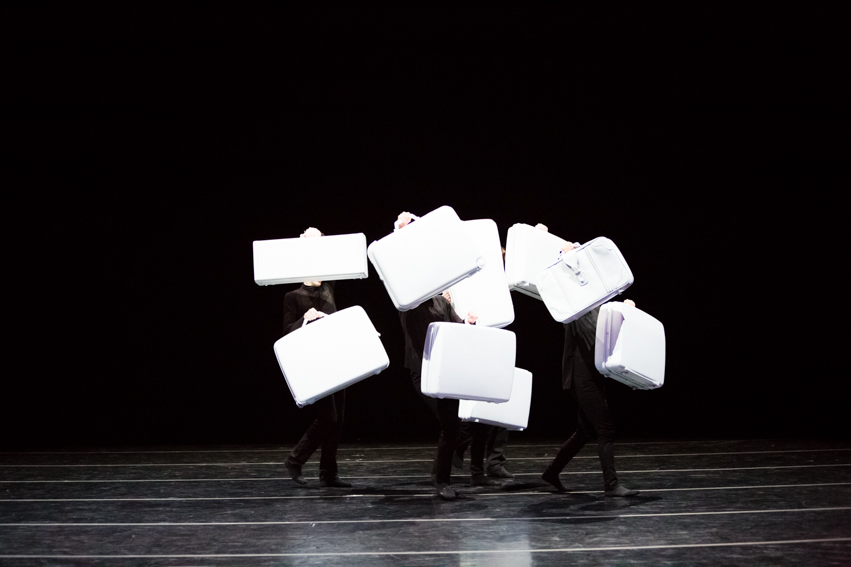

As Olivier says in the script, “That’s my baggage.” We all bring our own baggage with us to the theater, and who knows what is in those suitcases?