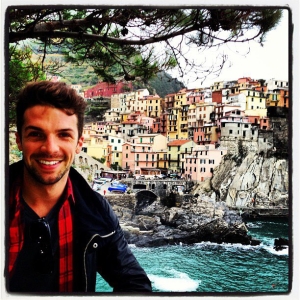

Until this season, Lucien Postlewaite, one of Whim W’Him’s founding members, was a principal at Pacific Northwest Ballet. Now he’s part of Les Ballets de Monte Carlo—plus guesting with Whim W’Him (weekend before last) and (February 9) as Roméo in PNB’s Roméo et Juliette, choreographed by BMC director Jean-Christophe Maillot.

“Can you tell me 3 things that are different about life in Monaco?” I asked on Skype.

Lucien laughed. “Everything!” he exclaimed.

There’s little stuff, like meters and centigrade, or the way you have to get really dressed up to go out to a nice restaurant or a club…

…then tricky bureaucratic complexities like visas, replacing a lost mobile phone or coping with a scooter accident

…and many other surprises, challenging or delightful.

Lucien hasn’t ever resided abroad before. When his Belgian-born husband, Whim W’Him artistic director Olivier Wevers returned to Seattle in September, Lucien’s new life began in earnest. “Living on your own makes you different, you don’t have a companion, a sidekick—and it’s easier that way. Without one you’ve got to motivate yourself to do things on your own. You have to act.” He misses “the connection to Whim W’Him and Seattle,” where he had “a full life” and knows it will take time to make something comparably complete and vital elsewhere. He is not, however, “going to or intend to create a replica.” He says, “I am trying to be okay with being away from Olivier all the time,” and allows that it’s hard. “But I am also enjoying finding out things by myself,” he says and adds that “living on your own, there’s a lot more time for reflection, which is good at this point in my life.”

Getting used to an unfamiliar living situation, traffic patterns and shopping habits; making connections with colleagues; negotiating new ballets, working schedules, and the joys and longueurs of touring—most of it in a second language—all are part of the new experience.

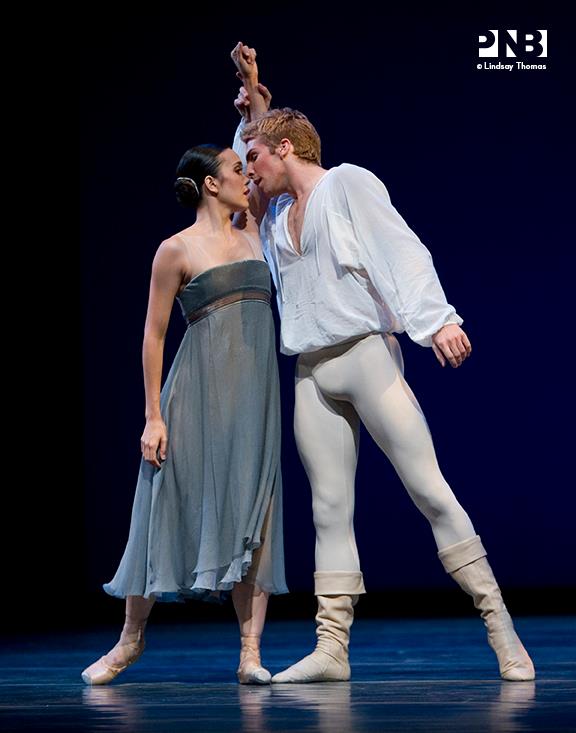

with Noelani Pantastico in R&J

Lucien already had a few friends at the MC ballet (such as Noelani Pantastico, with whom he had learned the Maillot R&J in Seattle and with whom he will reprise the role in Seattle on February 9), as well as acquaintances from earlier visits.

“Dance is such a small community,” says Lucien. “Communication is easy at first. ‘Where did you train?’ ‘Who were your teachers?’ ‘What’s your background?’”

When he was in Pittsburg a while back, for example, because he’d been in the original cast of R & J at PNB, people said, “Oh, you’re the Seattle Roméo!” and so he was neatly pegged, he filled a niche in their minds.

Of course making closer friends is more complicated and time consuming, especially in a different language. Every society, even each sub-culture, has its own rhythms, freedoms and rigidities. Like a new ballet, it takes time to learn a new way of life.

At Monte Carlo there’s no predictable schedule. You’re lucky if you know a day in advance what you’ll be working on. It’s also much more a large group activity, the whole company assembling together, rather than the frequent smaller rehearsals Lucien was used to.

Company class at Les Ballets de Monte Carlo is taught on a two-week rotation with guest teachers, a couple of them from Italy. The language they use depends on what’s comfortable for them, but mostly it’s French. Lucien already spoke some French; ballet is a universal language; and the names of ballet steps are French.

Yet he’s found it oddly difficult to work in. Lucien muses about how the brain in his body normally learns a piece, but now to pick up new work, he must first translate through a different part of the brain. Picking up combinations is harder under these conditions too. True, ballet is a known language for him; however, styles (of country, company, choreographer) vary. Steps are put together differently at Monte Carlo;

the accent is isn’t the same. Especially at the start, Lucien was pretty tired by the end of the day. “But you just do things, put one foot in front of the other.”

As time goes on, he’s grown into this life, made connections, and enjoyed learning new roles—in Vers un pays sage, a repertory piece of Jean-Christophe Maillot to John Adams’s Fearful Symmetry; the prince in Lac (BMC’s Swan Lake); and Lysander in their version of Midsummer night’s Dream, Le Songe—as well as touring with the company, to Brazil last fall…

…and now in Switzerland and France. BMC is a touring company, and being on the road is part of the life.

And yet, for all his great strides in adaptation, Lucien says, in some ways his move didn’t seem quite real until — after he’d had some time on his own — Olivier, his parents, and his sister came to Monaco for Christmas.

By then, on his own and with the help of friends, he’d formed new habits, made discoveries, explored places, and found things to show them in person or to do together, as you can’t by Skype, phone or email. Maybe, he confesses, he had been a bit afraid. What if he didn’t want to come back? But now he has embraced the idea that “life here is just different,” and having two different selves and lives is in itself exciting. Although in Seattle he had a clear sense of what was normal, in his new circumstances, “There is no normal. Normal is that it’s always changing. You go to work, not knowing what to expect, but trusting that it will be fruitful and rewarding.”

Next post: what do hands mean to Olivier?