We all know what a difference interpretation makes to dance works. Indeed it’s one of the characteristics of good choreography that it can be danced and viewed from multiple perspectives. Annabelle Lopez Ochoa’s L’Effleuré, the third piece in Whim W’Him’s Third Degree program last month, is a perfect case in point. My favorite dance critic, the New York Times’ Alastair Macauley, wrote a disgruntled review of the Jacoby and Pronk program at Jacob’s Pillow (2010) in which L’Effleuré premiered. “Here,” he sniped, referring to the entire program, “the flashy surfaces of the dances are all that’s going on in terms of serious expression.” Macauley was much put off by what he saw as a combination of “the drop-dead cool of supermodels” and audience manipulation. He concluded, “The mind has nothing to retain but good looks and wow effects.”

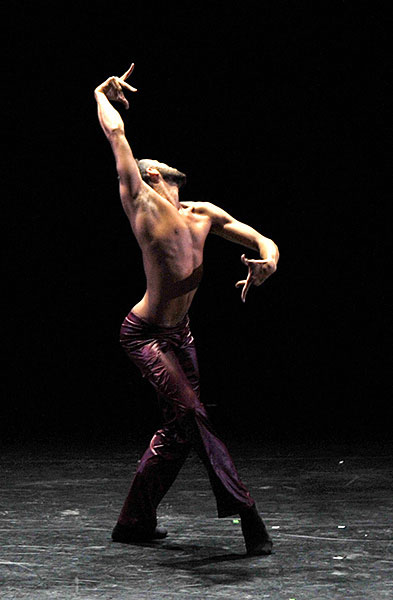

In watching and re-watching a video of Rubinald Pronk dancing L’Effleuré—well before reading the above review—I have to admit to being put off by what came across to me as the preening exaggerations of the dancer in this solo.

I remained a little uncomfortable with the piece even after reading Annabelle’s words about it. “Rubinald is an artist known for his strength and forceful dancing. I’ve known Rubi since he was 14 years old and I have watched him develop into this forceful artist. We have worked together once before and this time I wanted to make a piece that would show his softer, tender side. Like the king of roses.”

When I spoke with Annabelle in person later, while she was in Seattle teaching the part to Andrew Bartee, L’Effleuré began to make more sense. She talked about a king, like Louis XIV, so separated out by power and the etiquette associated with his exalted position that he has no normal life. This solo catches him in a rare moment where his loneliness, insecurities and vulnerability war with his deeply imbued imperiousness and self-regard.

As I observed Andrew learn the technically demanding role, the piece took a new dimension. Andrew is a versatile, as well as thoroughly modest and non-flamboyant person, choreographer, and dancer. He can convey seriousness of purpose (in the subtle and complex relationships of This is real., the piece he choreographed for the same Whim W’Him program) or carry off broad-brush comedy (as in his portrayal of Gamache in Pacific Northwest Ballet’s Don Quixote). Low-key humor (as in Whim W’Him artistic director Olivier Wever‘s Flower Festival) is a central Andrew characteristic, in work and life, and in performance it serves beautifully to defuse any hint of personal grandiosity or narcissism in his portrayal of the rose king in L’Effleuré.

At first, with little time to rehearse, Andrew struggled after the fluidity and assurance the role required. And then it was as if, in watching him master the tricky movements of the ballet, I observed him grow into the lonely ceremonial role of a king in a highly structured and artificial court. Rather than feeling like an exercise in swagger or preen, it was a journey of discovery by a young king, of both his dignity and his limitations.

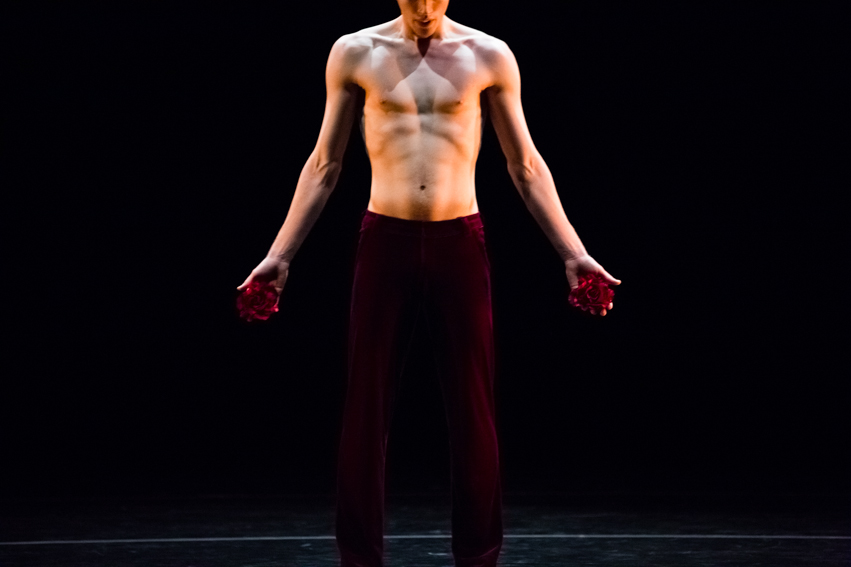

The results wowed all the critics who saw it. Michael Upchurch of the Seattle Times captures the nuanced layers, as well as the humor in Andrew’s performance: “L’Effleuré opens with Bartee in gleaming half-silhouette… The variety, control and detail of his actions, as he unspools himself in response to the music, are truly mesmerizing. There’s a latent violence in his eddying elegance, too, that lends the piece a stinging edge. The crowning touch: he performs the whole thing with a red rose clenched in his mouth (let’s hope someone trimmed the thorns beforehand).”

In the words of Seattle Dances‘ Anna Waller, “L’Effleuré, a solemn, noble solo, featured Bartee in red velvet pants and a deep red flower in his mouth and in each palm. The choreography demanded much clarity from Bartee, and he certainly delivered, deftly interspersing subtle, sinuous body ripples with clean balletic jumps and turns. Many times, he posed standing or in grand plié with his palms facing outward, so that all three flowers were visible: a pared-down vision of splendor…”

City Arts‘ Rachel Gallaher noted: “This piece mixes slow elongated movements of extension with small, quick footwork and transitions. With a rose in each hand (and one in the mouth), Bartee is mesmerizing—the continual return to a deep grand plie centers the piece, bringing it back to a place he can once again expand from, renewed with a new energy.”

Meanwhile, Michael van Baker had this to say:

“The light seems to drip down planes that are the front and back of Andrew Bartee, at the outset of L’Effleuré. Lighting designer Michael Mazzola catches Bartee from all angles throughout the course of Annabelle Lopez Ochoa’s dance piece, whether ‘elastic technician’ Bartee is soaring in a leap or sinking to his haunches in a grand plié, pulsing slightly to a rhythm like breathing or heartbeat. A sinuous movement travels slowly through his core, a leg extends skyward, he pirouettes — all with the gravitas of someone not simply at home in his skin, but almost too-exquisitely aware of it (with his back to the audience, Bartee manipulates his shoulder blades, and skin transmits the subcutaneous movement).

“L’Effleuré is a mash-up of referents,” van Baker continues, “it’s French for lightly touched, or caressed, but the program notes mention Louis XIV, the Sun King, too. The strutted torsions are about a muscular elegance, the rose-petal palms and rose-mouth advertising an easily-bruised sensitivity. (It looks great, but Bartee confesses afterward he’s mainly trying not to drool as he bites down on the stem.) At one point, Bartee sinks forward on his knees, his palms up as if in supplicating prayer, and then they look like rose stigmata. The music is Vivaldi’s ‘Stabat mater dolorosa,’ so the stigmata may not be unintended, though here they are transformed.”

I’m very curious what Alastair Macauley would make of Andrew Bartee in L’Effleuré.