Everyone likes to bask in accolades, but what can/should artists do to process criticism? How determine what to take to heart as fodder for growth, and what to shrug off as irrelevant or misguided?

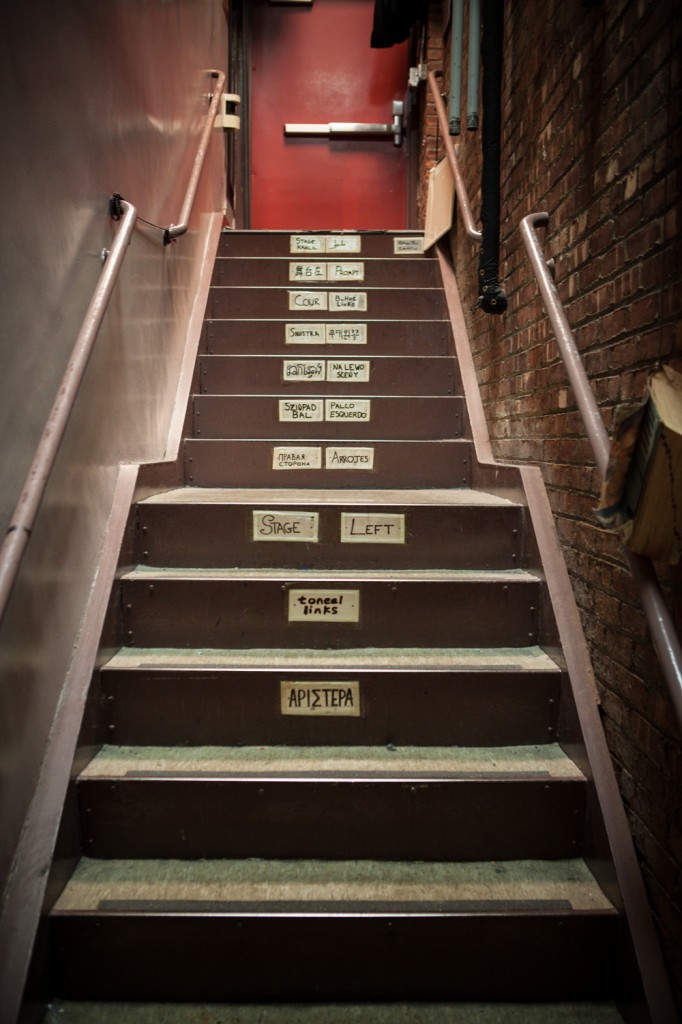

Whim W’Him’s first performances as a company—of three works by artistic director/choreographer Olivier Wevers—took place in January 2010 at Seattle’s On the Boards. OtB is a venue where resolutely contemporary dance is expected, and some audience members took strenuous exception to (among other things) Olivier’s use of pointe shoes because of their association with 300 years of ethereal princess ballerinas. An interesting discussion of gender roles and women in dance ensued.

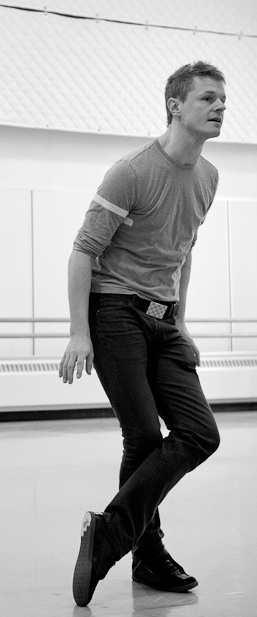

On August 12 and 13 of this year, Whim W’Him performed in Joyce Theater’s Ballet v6.0, a festival that presented “a range of ballet styles from neo classical to contemporary” by “some of the country’s most exciting young dancers and choreographers” who are “creating work outside the traditional large company setting.” Olivier was warned ahead of time that The New York Times wouldn’t like his work. And sure enough, that’s just what happened. Although Alastair Macaulay’s review of Whim W’Him garnered coverage on the front New York Times Arts page (and an inside page), along with two photos, his assessment ranged from tepid to disapproving. “Each piece, however, is limited in both dance and gesture” or (of The Sofa) “Watch and you find Mr. Wevers is interested in only the most superficial aspects of the music’s timing. Set against this score, his relationship games become like graffiti scrawled over a masterpiece.” (New Ways With Ballet Vocabulary Are Mirrored in Relationships, August 14, 2013)

As a sort of informal historian of Whim W’Him, I can’t just ignore negative critical evaluations. Yet how react to them fairly? After all, I only signed up for the (unpaid) job of creating and writing this blog, because I was already enthusiastic about Olivier’s ideas in forming his company and wanted to help describe and/or articulate its people, projects, and trajectory for others. It’s true that I observe rather than actively participate in Whim W’Him’s creative process, Yet many people would likely say I’m too committed to the company and too hopeful of its success to be “objective.” So do I have any hope of sifting through reviews and discerning which observations are truly valuable, which wrong-headed, and which it’s too soon to evaluate?

For that matter, does anyone?

Don’t worry, I’m not trying a reductio ad absurdem tactic, sidestepping real issues by blithely asserting that no one is unbiased so there’s no point in even pretending. In different ways, everybody—from choreographer to dancer to first-time dance-goer to veteran audience member to distinguished critic—faces the same questions about quality: How does one measure one’s own gut reactions (rooted in innate likings and personal transformative experiences) against contemporary fashion, the words of other viewers, marketing spin, and the cacophony of everyone along the way citing scripture for their own purposes? The problem of objectivity in the arts is always with us, especially in transitional moments like our own. Answers to it have to be found along a continuum.

In trying to tease out ways to think about these questions, it occurred to me to look at another transitional period in dance history and learn a bit more about how a not-yet-consecrated talent, like George Balanchine’s in the 1950s, was received by New York critics. Due to the wonders of the internet, a pertinent blog post by Ryan Wenzel popped up at once (Before They Were Masterpieces: 9 Negative Early Reviews of Balanchine Ballets—he found his references in “Nancy Reynolds’ invaluable book Repertory in Review: 40 Years of the New York City Ballet,” 1977 ).

It is an enlightening (and amusing) exercise to compare Macaulay’s disgruntled statements about most of the Joyce v.6.0 choreographers to remarks by then pre-eminent critic John Martin on Balanchine in The New York Times of September 9, 1951: “Apollo never will, in all probability, be popular. For

Walter Terry another highly respected critic of the era wrote about Prodigal Son: “There are portions which are deeply touching, superb in their inventions; there are others which are appropriately and believably erotic, and there are others which must be classified as unadulterated foolishness, dramatically and kinetically. Unfortunately, the foolish or the dull passages predominate.” (New York Herald Tribune, February 24, 1950). And so on.

Of course there have been plenty of artists, scientists and future masterminds in all fields who went unrecognized in their own day, or at first. And many once highly touted talents are forgotten within a few years, or even months, of their greatest successes. That George Balanchine sometimes went under-appreciated early on proves nothing about the future of Olivier Wevers’s choreography or Whim W’Him or any of the companies or dance-makers of Joyce v.6.0. But the exercise of glancing at the past points out the relativity of criticism and highlights how easy it is to view with suspicion what will turn out to be fruitful new directions.

Reviews of dance performances, even by eminent critics, often seem to me more like interpretations of Rorschach blots—or one of those drawings that shows an old crone when looked at from one angle and a young woman from another—than impartial assessments of measurable quality. Critiques can say at least as much about the observer as about the object.

In the on-going experiment of dance art, we don’t know what will stand the test of time. Will socks-instead-of-bare-feet-or-ballet-shoes turn out to be a marvelous and lasting way to nurture fluidity, speed and new forms of movement—or just another fad? What kinds of partnering will grow from greater gender equality and less sexual stereotyping? Will new wine worth drinking pour out of the classic old bottles? Or will the bottles themselves have to be re-engineered? We’re in the midst of a highly volatile period. Many cry out for a new Balanchine to save and define 21st century dance, as he did mid-20th ballet. Or a new Graham or Judson or Twyla, if you’re of a different persuasion. In the splintered world of our present, there is less and less a unified balletic or contemporary canon, and little reason to suppose we’ll return to mining single veins of received wisdom.

Tastes change. Styles and the names for them change. What critics and audience expect and want from the dance they see changes. If the title of the Joyce festival had been “Modern Dance v.6.0,” would Macaulay have written of Flower Festival, “It’s odd to see two skilled ballet dancers who are given so little of the kind of ballet dancing this music cries out for”? Surely he is not saying—is he?—that there is only one, quite narrow range of historically determined ways to respond in dance to certain pieces of music?

But quite aside from the NY Times article, let’s not lose track of other, more nuanced published reviews*, as well as the many positive audience and dance world reactions to Whim W’Him at the Joyce. Some excerpts from letter Olivier sent to the dancers after the note a number of these latter:

- “Most of you saw Wendy Perron’s (Dance Magazine’s editor in chief) tweet right after Tuesday’s show: “Wow! The choreography of @Whim_WHim@TheJoyceTheater was terrific — especially ‘Monster.’ Real inventiveness, musicality, unexpected emotions.”

- Portland Presenters White Bird absolutely loved it… Their words: “it’s a great show, and your dancers are beautiful!”

- The Vice Chair of the Joyce Board and his wife came backstage right after the show to meet me. They absolutely adored it, and are quite a charming couple. They were both very impressed, and said they were so proud to have had us, that it is what makes the Joyce such an amazing theatre.

- I also got lots of feedback from the Joyce staff members. They all see lots of dance and said we are fresh and engaging!

- Flower Festival has attracted a lot of interest from some presenters and festivals

- The Director of the Joyce called me on Wednesday to congratulate me again, he really liked the company and the show.

- I also received a lot of very appreciative emails from dancers that auditioned. They praise your [the Whim W’Him dancers’] generosity and the entire process.”

Perhaps choreographers and performers, faced with downbeat or indifferent viewers, simply have to practice a little positive thinking—or healthy denial—finding ways to feed on encouraging responses and absorb useful criticism without letting their vision become clouded by skeptics. Real change comes slowly. Patience still is a virtue, even in our impatient times. We need to wait and watch and enjoy the wonder of not knowing the path ahead or what will come next or what will stay.

*•Dd Response: Week 2 of Ballet v6.0 at the Joyce | DIYdancer

•Whim W’him: Ballet 6.0 at the Joyce Theater…. | NYC Dance Stuff

•Whim W’Him, Joyce Theater, New York | FT.com

•Ballet v6.O Festival – Whim W’Him, BalletCollective … | Dance Tabs