Last week I flew back from the east coast by way of Michigan, to spend three days shadowing Whim W’Him artistic director Olivier Wevers as he worked on a new Midsummer Night’s Dream for Grand Rapids Ballet. GRB‘s facility is impressive,

a handsome all-in-one building housing rehearsal space, offices, the ballet school and a 300-seat theater.

The company could not have been more welcoming—artistic director Patricia Barker, her husband Michael Auer who teaches for the company and is working on development among his many jobs, the wonderful dancers, donors like Melissa & Michael Lojek and Marilyn Titche (who kindly put me up), and the staff, from Melissa Leitch up in the top floor costume shop to marketing & design director Amber Stout and the others down in the first floor office, as well as company & facilities manager John Ferraro, who seems to be everywhere at once. My stay also coincided with Grand Rapids’ ArtPrize festival and the ballet’s Season Kickoff gala, plus I got to spend a lovely morning at the astonishing Meijer Gardens & Sculpture Park. Even the weather co-operated.

But enough effusions already! Let’s take a peek at what Olivier has been concocting in Grand Rapids. These were the last days of a month’s residency, which was previewed and summed up in a performance at Saturday’s gala of his new ballet’s culminating pas de deux. Yuka Oba & Nicholas Schultz danced Titania & Oberon, king & queen of the forest fairyland where most of Shakespeare’s play and all of Olivier’s rendering (to be called simply Midsummer) take place.

The older versions that balletomanes know and love best are George Balanchine‘s 1962 A Midsummer Night‘s Dream…

…and Frederick Ashton‘s 1964 The Dream.

Balanchine, somewhat surprisingly for those who associate him with plotless ballets, cleverly and touchingly stages a good deal of the play’s convoluted plotting in Act One, although he reverts to “abstract” form in his second act, where a magnificent classical final pas de deux is danced by Titania and a cavalier unrelated to the story. The sets— whether in the original New York City Ballet production or in Pacific Northwest Ballet‘s lavish and fantastical 1997 re-design by Martin Pakledinaz—evoke our customary fond expectations of fairies and moths, flowers and sprites.

Ashton’s one-act Dream drops some of the backstory and focuses on the plight of two sets of human lovers, the arguing fairy couple, and a hapless Bottom-turned-donkey.

But visually it still brings to mind our ideas of a classic fairy tale. In a review of a 2002 New York staging, critic Mary Cargill wrote that Ashton’s ballet was modeled “on early Victorian fantasies. Ashton’s choreography for the corps is an elegant and witty commentary on the period, with quick and silvery movements, and a soft, flowing upper body, with delicate echoes of the Romantic style.”

The piece now being choreographed for GRB is ballet for the 21st century.

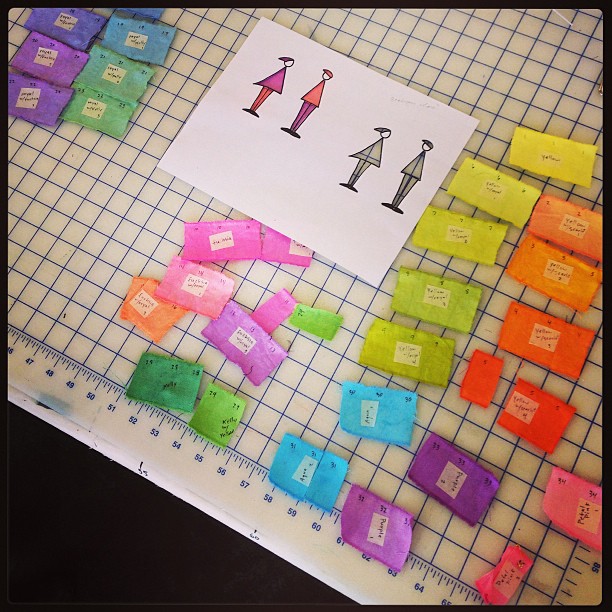

In it, Olivier pares down the narrative even further, explores unresolved tensions between Oberon and Titania, and radically strips away the usual green-and-mossy-

bower setting in favor of a totally white stage, with all the characters clothed in white except the mortal lovers and (to some extent) Bottom.

But lest you fear that with the departure of decoration, magic too will flee, let me hasten to note that the colors to be employed will make vivid and dramatic contrast to the background, while otherworldly lighting effects will be conjured up by that wizard of the illuminated stage, Michael Mazzola.

The movement vocabulary, too, is a far cry from the prettiness so often associated with danced versions of this story. But in calling forth the strangeness of enchanted-forest beings, while exploring the subtleties and confusions of all-too-human relationships, Olivier’s choreography summons its own wild beauty.

Olivier will be back in February to finish creating this complex and fascinating ballet.

In the play, the mortal lovers and the viewers are urged to think of the whole thing as nothing but a dream (with perhaps the implication that it was no such thing). While in both Balanchine and Ashton versions, the dream of the title is simply assumed, for Olivier the dream belongs to a boy named Nick Bottom… but more of that in a later post.