What makes a good dancer? I recently asked Olivier Wevers, founder, artistic director and chief choreographer of Whim W’Whim. “It’s like a recipe,” he replied. “Different flavors—for a curry, say, is it less or more spicy? and what different vegetables or meat will you use?”

Some ingredients, though, are surely needed in the preparation of any fine dancer. Olivier’s list includes:

•Intelligence

•Talent—both natural and learned

•Experiences that you have—”like in your piggy bank, your savings”

•Physicality—body proportions, feet—”That’s another whole set of recipes…”

•Musicality

•A high level of ambition and persistence—a hunger to succeed

•Pain tolerance—“being a bit of a masochistic person”

•Willingness to take physical risks

•Uniqueness—”What you add—your weakness can be part of it. A perfect dancer is a boring one,” Olivier believes. “I love to see the flaws become beautiful. It’s exciting. Embrace your flaws and embrace defeats.”

A choreographer needs many of the same qualities as a dancer. Body type and condition are rather less important, though being in good shape is certainly helpful for one like Olivier who relies on demonstrating what he wants. Pain and taking risks are part of the story, too, but tend more to the mental than the physical. A choreographer needs a keen musical ear and discriminating eye. Years of observation are required to learn the ways bodies can move, all the vocabulary of different dance forms—the tools of the trade. And finally, there are the notions, the images, what the dance-maker has to say. A choreographic imagination does not make a direct representation of ideas or events, but creates moving (in both senses) metaphors that communicate with dancers and audiences alike.

Olivier took his first stab at choreography in the early 1990s with a duet for him and Kaori for the Royal Winnipeg dancers’ choreographic workshop. “I was very disappointed with it,” he says, “Afterwards I was done with choreography.” It wasn’t until about ten years later at Pacific Northwest Ballet that he tried his hand again at dance creation. He talked to directors Kent Stowell and Francia Russell, who agreed to let him work with students in the studio, which led to a number of pieces for PNB’s Choreographers’ Showcase. Olivier’s appetite was whetted. He looked forward to and enjoyed the process. Over the next few years he found other choreographic opportunities in and out of town on a small scale for individual pieces.

Meanwhile friends, especially dancers he was working with, told him he ought to develop his own voice in his own company. “It took a while to get me to do it,” Olivier confesses. “It took their encouragement and support.” Exploring the idea, he heard from friends who were running companies or who had started their own.

But when Olivier got a fellowship for choreography from the Seattle based Artist Trust in 2009, it came in essence as a vote of confidence and solidified the idea of starting his own company. “I can do this,” he thought. But once past “I can” and “I want to,” he was faced with “Now what? How do you actually do it?”

The task was daunting. For all the endowment and accomplishments of a seasoned performer, many other skills are required to start and nourish a successful company. Whatever talents and experience a dancer-choreographer possesses, they will doubtless be insufficient, and perhaps sometimes even at odds with those needed for arts entrepreneurship and administration.

“There’s so much to learn, so many layers,” Olivier remembers, “fund-raising, legal stuff—permits from city and state, building a website, email blasts, the blog, finding performance venues, recruiting volunteers and coordinating their efforts and on and on.” All of this was quite in addition to the basic mission of the company: To provide a platform, centered on choreography and dance, for artists to explore their craft through innovation and collaboration. In addition to the quintessential time in the studio with dancers, making dance for his own company also involved figuring out the repertory, auditioning and hiring dancers, planning rehearsals at times that fit dancers’ schedules and available studio time.

Perhaps the first concrete step was to apply for tax-exemption. In this he was helped by the lawyer husband of a dancer friend, who advised him that if you wait until you have a company before getting IRS 501(c)(3) status as a nonprofit, it is harder to get.

To start any enterprise, of course, you need money and need to learn how to present your vision in a way that will convince others to invest. In October 2009, Whim W’Him held its first fund raiser. And then, in January 2010, first performance of Whim W’Him took place at On the Boards in Seattle. The company was launched.

At the start, much of the work was on Olivier’s own shoulders. It was physically, mentally and psychically exhausting. But all along, Whim W’Him has benefited from the faith and help of many people. At each stage, Olivier emphasizes, the company has depended on the invaluable help of friends-turned-board members, volunteers in many capacities, and interested parties willing to contribute crucial skills. In the beginning it was personal acquaintances. Throughout the early process of forming Whim W’Him, Olivier went to people who already believed in him or at least knew of his work and asked for help, all the while struggling to learn new skills in areas and to juggle all the myriad tasks involved in a smoothly running enterprise.

Now executive director Katie Bombico and the board do a great deal of essential work on their own and together. “It takes such a big load off of me,” Olivier says, to have a team working behind the scenes as well as a close-knit group of dancers on salary with set studio times and no more need to work around complicated individual schedules.

Working closely with O now since the start, I’ve noticed again and again some salient characteristics of Whim W’Him: the emphasis on everyone working together as a close-knit ensemble, a strong sense of fairness and the shared appreciation of a certain whimsical sense of humor. These qualities are not an accidental or mere by-product, but embody a core commitment. They are the essential engine that makes the company grow and thrive.

I asked Olivier what, in the first five years of Whim W’Him, were the biggest challenges he and the company had faced. His answer: “Fund-raising. The stress of being responsible for the dancers’ well-being and livelihood, raising enough for that. Balancing all the different needs of grants from city, state, region—stress, growing, learning, more stress, managing stress. Learning step by step and to sustain it all, learning to follow through.” There’s also the question, naturally, of dealing with criticism. At first that was physically and emotionally hard, Olivier says. But like anything else, one learns. “You have to do what you believe in, try to realize your own vision. Not everyone will agree with it or like it. I don’t do it for the people who don’t like it.”

He adds, “It’s a big puzzle. There are no ready answers, we keep putting in pieces.” It’s quite a good analogy, only it’s a tricky sort of jigsaw puzzle, where there’s no picture on the box, only the images Olivier and his collaborators have in their heads. Not all the pieces are there to start with. They have to be carved out…

Well, how about the rewards, I asked Olivier. Is it all worth it? “At the beginning,” he says, “we were surrounded by friends and known followers. Now I am amazed at how many of the company’s followers are new to me, new to Whim W’Him, new to modern dance, new even to dance. It’s expanded way beyond my own circles.” At performances and other places, in person, online or in print, he meets people he has no personal connection with. They see things he never thought of before in the work. Also thrilling are “Putting together programs, finding new choreographers and music, working with the dancers, making a piece that touches people, and hearing those audience responses.”

And then there’s the fluidity and change that is the one constant especially in the constantly changing world of dance, special dancers retiring or moving on to other things. Is that hard to cope with? “You have to be able to let people go, put new dancers in roles created on others. That’s the reality of dance. It’s not static, it’s alive!”

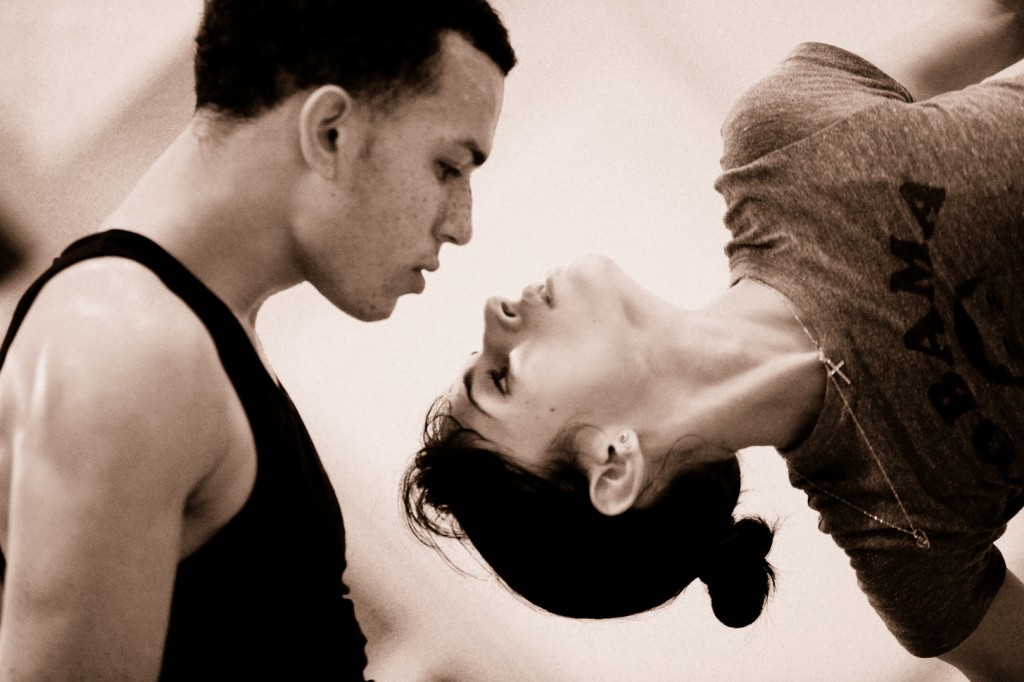

Photo Credits: First image of Olivier by LaRae Lobdell LaRaeLobdell.com | Environmental Portrait Photographer. Second image by Angela Sterlingfor Pacific Northwest Ballet. All others by Bamberg Fine Art Photography