I’m sitting in a hotel room at 11 pm in Umeå (where Stieg Larson lived), northern Sweden.

I’m sitting in a hotel room at 11 pm in Umeå (where Stieg Larson lived), northern Sweden.

There is a huge birch tree outside the window and a red brick and slate steeple that dates from just the time of Ibsen‘s Hedda Gabler (1890). The sun still hasn’t set, and I wonder why they have Daylight Saving here—if only it could be saved for winter!

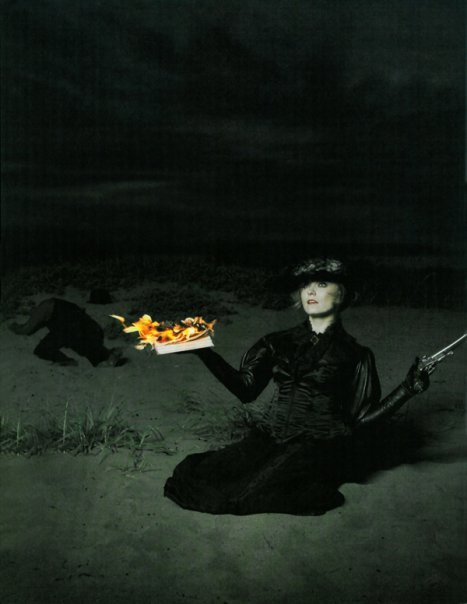

In our room are two photos that could have been taken of a set for Hedda.

All of which is by way of Nordic atmosphere—to set the mood for talk of the latest Hedda interpretation by the prolific and protean Marya Sea Kaminski.

As I write, Marya is performing at Hugo House in Riddled, “An immersive rock musical, that takes on love, firearms and Bonnie and Clyde,” for which she wrote the book and collaborated, with Sean Michael Robinson, on the music. The brash, in-your-face Riddled, one might think, is about as far a cry as you could get from Hedda Gabler, Ibsen’s convoluted play of late nineteenth century oppressed/repressed womanhood.

But this summer Marya seems preoccupied with girls and guns. In both productions, pistols play a central role.

For Intiman‘s unusual version of Hedda Gabler—directed by Andrew Russell for the Intiman Theatre Festival (July 14-August 25, 2012; previews July 5 & 8)—Marya will both speak Ibsen’s words out loud and portray Hedda’s interior world through movement. Last Thursday was the first run-through of the play. “Exciting!” exclaimed Whim W’Him‘s artistic director Olivier Wevers, who is choreographing Hedda’s hidden interior, the psychic reality beneath her speeches.

In a 2010 interview with The Stranger, Marya noted the limitations for her of the Stanislavski method of acting, which feeds directly on personal experience. “I can think about my dog getting hit and get teary,” she remarked—until one day it doesn’t happen. When the tears don’t come, she said, “Then I’ve failed in two ways. I’ve failed to bring an honest emotion to stage, and I’ve numbed myself to that personal experience.”

Again and again, as I read reviews of Marya’s work and researched her bio, I was struck by this concern of hers for honesty.

Stanislavski, she said, when we met at last in person, has permeated American theater, even when it’s not consciously intended. As she also pointed out, Method acting provides “useful skills and processes.”

Stanislavski, she said, when we met at last in person, has permeated American theater, even when it’s not consciously intended. As she also pointed out, Method acting provides “useful skills and processes.”

But life experience and imagination are not the same.

A crucial insight, this, especially from a person much of whose own writing has been autobiographical in nature. Not differentiating between what happens to one and what one does with the experience is, it seems to me, like failing to distinguish between the ingredients of a cake (flour, eggs, sugar, milk, etc.) and the finished pastry. Success, even what one might call authenticity, depends on the right proportions, a skilled stirring hand, baking time, and some unquantifiable soupçon of individual inspiration, at least as much as on good raw materials.

In the same Stranger article, Marya warns that she’s about to say something cheesy:

“The more I learn about acting, meditation, life, and love, I realize it’s all the same thing.”

“What’s that?” the interviewer asks. “The answer is to be in your body at this moment.”

Could she say a bit more about this-moment-in-your-body? I inquired.

“I had a lot of physical theater training,” she replied. It taught her how “staying in your plan or thinking your way through” isn’t always a good idea. You are “sharing physical space with other actors” and with the audience. You need to be attuned to the mood and sensibilities of those around you.

This reliance on responding to the instant reminds me of what Olivier has often said his choreography not jelling when he comes into the studio with everything worked out ahead of time. Of course one has to have thought about the subject, letting the task at hand percolate down into the layers of the brain below consciousness. But there is something about spontaneity—the tension, the thrill of having to come up with something on the spot—that fuels his creativity, as it does Marya’s.

Marya Sea Kaminski has done Hedda Gabler multiple times (among them in an iconoclastic 2007 adaptation at On the Boards, called BlahblahblahBANG! A Pistol Fit in One Act, produced by Washington Ensemble Theatre, of which she is a founding member). Marya is intensely glad at this chance to revisit the play. For the Intiman summer festival version, she, Olivier, director Andrew Russell and the other actors have pieced together their own translation. They have come up with a very “economical” script, she says. In a radical approach, they’ve taken out not only repetitions but the psychological subtext of Hedda’s part. That is what her dance component will suggest.

The trap Hedda finds herself in is a peculiarly female one, with which, to some degree, she colludes. She inhabits a milieu where women are viewed as “characters of perfection,” not allowed to slip in their propriety, nor to foster private interests or strive for personal achievement, relying instead on men for income and sustenance—material, mental, moral. Always, for anyone but especially a woman who steps outside the line, the threat of scandal hangs overhead.

Marya had some concern about there being a male director and male choreographer for this show. She was not sure if they were going to be able to journey into Hedda’s mind. “But,” she says with a lovely open smile, “we’re working beautifully together.”

Marya likes to think about the play and its principal protagonist in relation to a contemporary standpoint. The obstacles to Hedda’s being liked or being happy really might not exist today, she believes. So how can modern audiences connect with this difficult, often disagreeable, and even downright dangerous figure? “They might sympathize with her dilemmas if not her decisions and choices,” says Marya.

And how is Hedda Gabler to be staged? The conception of this production is an interesting combination of external leanness and rich interior convolution, the ultra-pared-down alongside the intricate and elaborate. Hedda never leaves the room where it all takes place. The costumes will be “extravagant, quite glamorous.” Opulent. “These people,” Marya says of the characters in the play, “are in their prime.” Beyond costumes, “There will be a very spare setting, but not underdeveloped—a very specific environment.” And it is this care for specificity, that marks Marya’s approach, as it does Olivier’s—their common commitment to extreme, honest particularity as the point from which the art of individuals can open out into universality.

Up next: The rehearsal process and plumbing the depths of Hedda Gabler.