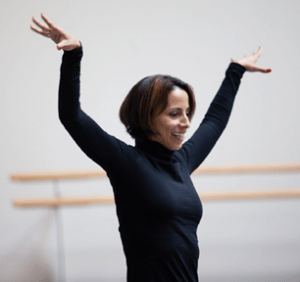

No question, Annabelle Lopez Ochoa is the sort of person you’d like to have in your life during a pandemic. Fiercely alive, wildly inventive, wide-ranging in her artistic interests, she greets the unknown with humor, grace and depth. On March 1, Annabelle was in Oklahoma setting her evening-length ballet Vendetta: A Mafia story on the Tulsa Ballet, when the opening was postponed, first until May, then until the end of October, and now until March 2021.

Although slated to fly next to Seattle to create a piece for XALT, the last program of Whim W’Him’s 10th season, she hurried back to Amsterdam. On arrival she didn’t feel well and thought she might be sick with the virus, so she quarantined herself and took her temperature every day. “It was probably just jet lag,” though, and for a while some time out seemed good. “I don’t think I’d been home that long since 2008,” she says. “I was yearning for a sabbatical.” She did a deep cleaning of her apartment, then painted it in vibrant colors. But it’s not in Annabelle’s nature to let her real calling sit still very long, though, and as nobody knew when normal theatrical life would recommence in this upside down new world, she soon began concocting ways to create vital dance by other means.

Since then, she has choreographed and edited 8 short dance films, learning more with each one. A cameraman friend in Amsterdam who saw the first said, ‘You made a registration of a work I could watch on stage, it’s not interesting.” Annabelle, never put off by a challenge, thought, “I want to practice.” So, this spring and summer have turned into a crash course in learning-by-doing. Even before the pandemic, she was thinking in cinematic terms, as evidenced by an interview filmed in Tulsa, where she talked about her conception of Vendetta (originally premiered in 2018 in Montreal) as a series of movie scenes. With the help of her videography mentor, she has opened up her always fertile imagination to the creation of films that are not just archival records of performances that were really meant to be seen in person, but intentional artworks in themselves.

As an early adopter of film for the medium to keep dance leaping forward in trying times, Annabelle has called on her profound instincts for both using humor to thumb her nose at trouble and responding artistically to the dark and shattering turmoils of our time. In The Chicken or the Egg, Maine Kawashima and Sasha Chernjavsky of Tulsa Ballet contemplate that perennial conundrum in a 3+ minute film featuring an egg in its shell, a fried egg (plastic, I presume), and a fluffy live white chicken named Cotton Ball, who took to the spotlight without ruffling a feather.

At the other end of the emotional spectrum is Say Their Names created for two Dance Theatre of Harlem dancers Anthony Santos and Dylan Santos. For some reason I watched this first without sound and that was powerful enough, but to Nina Simone’s Strange Fruit, it is both disturbing and achingly poignant. A very personal creative reaction by dancers and choreographer together to Black Lives Matter, Say Their Names demonstrates the power of this short film form to connect in the moment to the world. ‘I am a mixed race child,” says Annabelle, “and grew up with some racism. The dancers aren’t choreographers but together they could find ways of saying what we are needing. “

Now Annabelle is working, at a distance (a long distance), with Whim W’Him again. Her fifth Whim piece, GRASSVILLE, has already undergone major changes. Rehearsals were originally scheduled in Seattle to start at the end of March, right after Tulsa, as part of XALT, the final show of the company’s tenth season opening. But by then the virus was upending all our lives. Whereas when the lockdown period began Penny Saunders had had a week or more of in-person time in the studio, and Artistic Director Olivier Wevers was in town and in constant touch with the dancers, working out how to proceed, Annabelle’s rehearsals had not yet started.

So, it was decided to postpone her piece until the fall and the Choreographic Shindig. Once that decision was made, Annabelle’s Zoom rehearsals began in toward the end of July. “For film,” she told me, “there’s a different take on how you make a piece. Because of it being via Zoom, I can’t prepare too much.” That turned out to be lucky for the current Whim project. Back in May, the idea had been for “an investigation of gender fluidity.” She added with a smile, “I always take the road of experimentation with WW.”

However, circumstances didn’t augur well for the success of this particular exploration. Annabelle quickly had second and third thoughts about the nature of the piece to be created. I tuned in early on and remarked to her a day or so into the Zoom rehearsal process (also via) what a big difference it made (after a couple of months without) to see dancers together inside the same studio, even if distanced and masked, she replied, a tad sharply, “Now they are back to their own houses. They were masked and too far away.” There weren’t the necessary interactions and relation between them. They couldn’t be as close as they needed to be. “The connection was bad. It was like teaching a class, not choreography.” In addition, of the current dancers, Annabelle has only worked with Jim. “It’s a question of trust.” How could she get to know a roomful of dancers without seeing their full faces, when they couldn’t touch or even approach each other. Backlighting of a studio with many windows made it very difficult for her to see as well. “So many obstacles to a piece of art being made!”

When we spoke again a week or so later, Annabelle said, “There was very much a disconnect. Choreography is intimate.” Gender fluidity, with its subtleties of direct interaction seemed like a subject much better to explore in more normal times, when there would be the possibility of fuller understanding, trust and connection, literally and figuratively, between dancers and dancers with choreographer in exploring such a subject. She talked about the Buddhist idea of living in the present only, the non-existent future, letting go of the past. Very humbling. It was up to me to let go of the idea.”

But she does know how to rise to an occasion, and so does costumer Mark Zappone. “For the original idea I had—at some point they would have needed to touch. So, I thought why not make a piece showing people not touching each other? In the dancers’ houses I saw plants. I asked Jim [Kent], ‘Can I use one?’” Jane [Cracovaner] had plants too. Lots. Annabelle also had plants—though all plastic (so they wouldn’t die). “I bought a lot. The desire to bring nature inside my home since I was cut away from nature in lockdown in an apartment in a city.”

On the next Monday she restarted with a totally new creation. “Maybe a piece on lack of contact with nature. You know me, a bit surreal…”

“I told them they’ll be wearing wigs of green. Transformed into our desires.” The dancers would have plants as heads, created by the ever-inventive Mark, who has conjured up an astonishing variety of greenery heads for the seven dancers.

“Funnily enough,” says Annabelle, “when I started to work with tiny little plants, it worked—it flowered.” The piece sprouted quite naturally in the short period available. The right idea at the right time.

It took a while to sort out the location—a borrowed for-sale house? or “one chair and one sofa or rent things or take furniture outside”? Finally, the apartment of the three newest dancers just joining the company became the scene, stripped to be as white and blank as possible.

Because of the nature of the piece, says Annabelle, “The dance is completely fragmented.” It’s like a species of pandemic-flavored counter-bedroom-farce, where no one ever ends up in the same space with anyone else, replete with running in out of rooms, opening and closing doors—all bringing out the whimsical in Whim W’Him, at a moment when we can use a little timely humor.