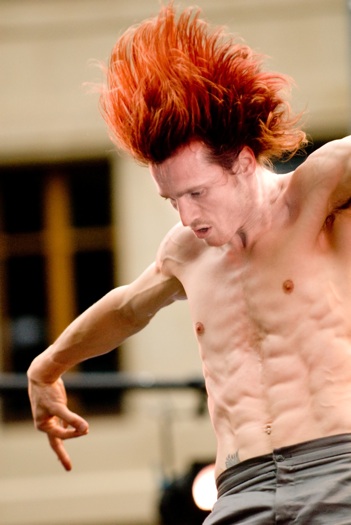

First impressions of Manuel Vignoulle in the studio with Whim W’Him:

strongly articulated movement and irrepressible, infectious energy.

He’s a living exclamation point who wonders “about spacing, physical challenges—what more can be done here? or here?” Within moments after the start of rehearsal he has the dancers running, leaping, spinning,

doing donkey kicks and somersaults, changing levels multiple times,

rolling, crumpling, sliding, stretching their bodies to the utmost,

laughing (in incredulity?)—and sometimes, at breaks, falling on the floor in exhaustion.

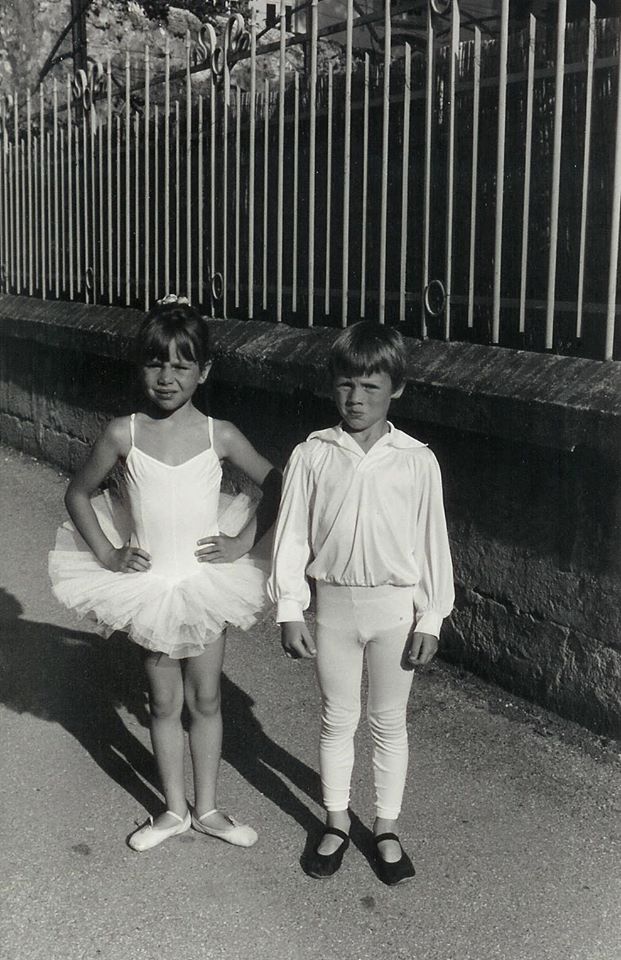

In childhood Manuel was, as he still is, “very active.” Along with his sister, in a class “with balloons and ribbons,” he started dancing when he was “really young, 2-1/2—dancing was good for channeling my energy.”

Ballet training began for Manuel at 6, contemporary dance at 9. He took gymnastics for 6 months, but didn’t like it much, so didn’t continue. At the age of 14 he entered the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique et de Danse (Paris) in contemporary dance. When he started, his idea of a “contemporary” choreographer, was Jiří Kylián (b. 1947) or Mats Ek (b. 1945), but those he studied there most were an older generation of modern dance makers, like Merce Cunningham (1919-2009) and José Limón (1908-1972).

The idea of making dances as well as performing them came to Manuel early. As a child, he reports, he had a tendency to improvise at the back of the classroom, rather than do what the teacher was asking. He was creating shows in his parent’s living room with any friends ready to join him. At around 9, he decided he wanted to be a choreographer, but his parents suggested that he dance for some time first, to acquire the necessary tools. “In the process,” he recounts, “I forgot.”

It was many years before he came back to it, but once he did, the twin strands of performing and creating dance have intertwined in his life ever since. Upon graduation from the Conservatoire at 18, he danced for 3 years with contemporary companies in Europe, then, at the age of 21, also began working as assistant choreographer with Redha, a modern-jazz choreographer.

Known for his success in the international entertainment industry and for large-scale opening spectacles of events like World Cup soccer, Redha is also recognized for his own modern ballets. Manuel worked with him on projects for television and film, in fashion, opera, and musicals, as well as in collaborations with Alvin Ailey (US), Het Nationale Ballet (Netherlands) and the State Theater Dance Company (South Africa).

The 4 years with Redha were a kind of choreographer’s apprenticeship for Manuel, at the end of which he felt it was time for him to strike out on his own. But rather than pursuing choreography just yet, Manuel was determined to follow a long-time dream of becoming a professional ballet dancer. He spent a year and a half dedicated to studying ballet in Paris with Dominique Khalfouni, a former étoile of the Paris Opera Ballet and principal of the Ballet National de Marseille.

Aiming to dance for The Forsythe Company in Germany or a group of similar renown, Manuel found himself, “back with 12 year old girls who were way better than I was.” He worked10 days out of the month “doing TV stuff for lots of money, which would pay for my ballet classes and auditioned everywhere—no luck.”

Short stints did turn up, as usual of wildly different types. As a guest artist, he traveled to South Africa to dance at the State Theatre, got to work with Forsythe on a few shows of Human Writes, with high-energy, decidedly unclassical La La La Human Steps for a 6-month opera project played at l’Opéra de Paris and at BAM (NY), and then Manuel was hired by the Ballet du Grand Théatre de Genève for 5 years.

After seeing him perform at the Joyce theater NYC with Geneva Ballet, Benoit-Swan Pouffer—then artistic director of Cedar Lake Contemporary Ballet and also trained at the Paris Conservatoire—showed interest and ended up offering him a contract for the next season. Manuel flew off to New York.

At the end of 3 seasons, however, Manuel says, “I had danced 17 years for others. Now it was time for me.” The universal advice, when he’d asked many other choreographers “How did you start?,” was to put some money aside. He had enough to live for 4-6 months, nothing particular planned, and felt “free, so excited. Life was full of possibilities once again!” Twelve shows of a duet of his—”better than 65 of someone else’s work”—led to other choreographing commissions in Switzerland. “It is hard to start a new chapter. What can I bring to it? Need to try to have fun. I ask, ‘Can we be crazier?”

The answer seems always to have been a resounding Yes!

In the 4 years since he began concentrating his formidable energies on choreography, Manuel’s work has been performed in France, Switzerland, Germany, Mexico, the US and Canada. His works have been commissioned by Ailey II and the Ailey School, Satellite Collective, 10 Hairy Legs (a company of 5 male dancers formed in 2012 by Randy James), Chicago Repertory Ballet, Peridance Contemporary Ballet Company, Steps Repertoire Ensemble, Rutgers University, various dance festivals, and now Whim W’Him. He also was teaching a good deal, but says “now I decided to teach less, travel more. If I have too much work, I feel I am a working machine and start to hate it. I need to be sure I’m well-balanced and creative in every new project.”

For more on Manuel and RIPple efFECT, the crazily imaginative and athletic piece he’s making for Whim W’Him, see this coming Saturday’s post.