In mid-April started on Whim W’Him’s final program of the 2017-18 season, TRANSFIGURATE with performances June 8-16 at the Cornish Playhouse at Seattle Center.

Artistic director Olivier Wevers and the Whim W’Him dancers began rehearsing his Silent Scream, a new work that has grown out of a short piece about Charlie Chaplin (1889-1977), danced by Tory Peil at an APAP (Association of Performing Arts Professionals) presentation in British Columbia several years ago.

There is a lot more to Charlie Chaplin than many people realize these days. In the early years of movies he was one of the most famous people in the world. Even now nearly everyone knows his name, while several of his films, such as The Gold Rush, City Lights, Modern Times, and The Great Dictator, are numbered among the greatest of all time. Andrew Sarris, in You Ain’t Heard Nothin’ Yet: The American Talking Film–History and Memory, 1927–1949, calls Chaplin’s creation, The Tramp, “cinema’s most iconic image.”

Due to his fame, box office pull and personal strength of character and convictions, Chaplin was one of the few artists who has ever had the opportunity to write, direct, produce, edit, star in, and compose the music for most of his own films.

Seven-year-old Chaplin (middle center, leaning slightly) at the Central London District School for paupers, 1897

But he didn’t start out at the top. Quite the contrary. In addition to, and often underlying, his work in film was Chaplin’s own harsh childhood experience in which his passionate political views were rooted. Growing up in a truly poverty-stricken environment with an absent father and an ill-starred mother, he was sent to the workhouse twice before the age of 9. His mother, Hannah Chaplin, who went by the stage name of Lily Harley, was an English actress, singer and dancer who performed in British music halls from the age of 16. But ill-health, physical and mental, dogged her throughout her life. Chaplin’s own first appearance on stage occurred at the age of 5, when his mother lost her voice and he went on in her stead. She was first committed to an mental asylum when he was 14 and spent the rest of her life in and out of institutions. Chaplin’s deep and visceral knowledge of the unfairness of life and the ravages of poverty permeated his cinematic work, in much of which silly slapstick comedy and genuine pathos combined to profound effect.

He was a performer himself most of his life, at first in music halls and on the stage, later in movies. At 19, Chaplin signed on to the prominent Fred Karno Company and toured with them in America. That was where the film industry discovered him and where he developed his little Tramp character. In his autobiography he describes the genesis of his quintessential persona: “I wanted everything to be a contradiction: the pants baggy, the coat tight, the hat small and the shoes large. I added a small moustache, which, I reasoned, would add age without hiding my expression. I had no idea of the character. But the moment I was dressed, the clothes and the makeup made me feel the person he was. I began to know him, and by the time I walked on stage he was fully born.“

Chaplin made Tramp movies with several different movie companies, before, in 1919, co-founding United Artists, which gave him complete control over his films. The next 20 years marked the era of his greatest popularity, wealth and adulation by the public. But with the Great Depression and the rise of Fascism and Nazism in Europe, Chaplin’s sympathies and interests became more and more politically charged and the contrast between comic and serious strains in his art more pronounced.

The Great Dictator, Chaplin’s first talkie film is a mocking portrayal of Hitler. David Robinson, a biographer of Chaplin, writes, “There was something uncanny in the resemblance between the Little Tramp and Adolf Hitler, representing opposite poles of humanity,” and quotes an article from the British Spectator magazine of April 21, 1939: “Providence was in an ironical mood when, fifty years ago this week, it was ordained that Charles Chaplin and Adolf Hitler should make their entry into the world within four days of each other.” The Spectator article continues: “Each in his own way has expressed the ideas, sentiments, aspirations of the millions of struggling citizens ground between the upper and the lower millstone of society,” and concludes that “Each has mirrored the same reality–the predicament of the ‘little man’ in modern society. Each is a distorting mirror, the one for good, the other for untold evil.”

That final speech of The Great Dictator is the centerpiece of Olivier’s Silent Scream. At the end of the movie, by means of a typically farcical Chaplin plot, an anonymous Jewish Barber is mistaken for the great dictator Adenoid Hynkel and delivers a 5-minute plea for humanity beginning: “I’m sorry, but I don’t want to be an emperor. That’s not my business. I don’t want to rule or conquer anyone. I should like to help everyone – if possible – Jew, Gentile – black man – white. We all want to help one another. Human beings are like that….”

The Great Dictator (1940) was a watershed moment for Charlie Chaplin. The 40s were filled with trouble. In the US, personal scandals (divorces, paternity suits, marriage to much younger wives) and political embroilment multiplied (cries of “Communist!” and an FBI investigation), eventually forcing him out of the country. He relocated permanently in Switzerland, where he continued his cinematic career, but not as The Tramp character, who by then had retired from his films.

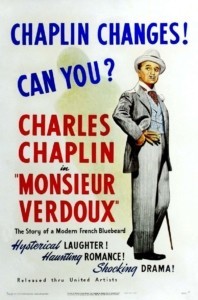

Monsieur Verdoux (1947), a dark comedy about a serial killer, marked a significant departure for Chaplin. He was so unpopular at the time of release that it flopped in the United States.

Yet even during this darker period, Chaplin never ended up destitute or forgotten like so many one-time stars, and his final marriage, to Oona O’Neill lasted 34 years, producing 8 children. In fact, Chaplin’s work enjoyed a strong revival during the final years of his life. He was made a Commandeur de la Légion d’Honneur at the Cannes Film Festival in 1971. In 1972, 5 years before his death, he received an Honorary Academy Award for “the incalculable effect he has had in making motion pictures the art form of this century,” while 2 years later, he was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II.

Because Chaplin’s first, and in many ways greatest renown, came in silent films, music was paramount, and much of Olivier’s Silent Scream is set to Chaplin’s own movie music. The rest of the soundtrack, beyond the Great Dictator speech, is being compiled (if that’s the right word) by Olivier himself. For example, he uses the sound when “you get to the end of an old movie reel during a projection and it continues spinning and makes that flapping noise as it goes round and round.” In a striking scene that flickers like an old movie with stop-action images of dancers kissing, punching, posing in Chaplinesque fashion, this relentless tick tick tick epitomizes how routine and mundane daily life eats up our existence.

Both laughter…

…and pain will be embodied in Silent Scream.

And each dancer will embody some aspect of Chaplin’s multifaceted characters, onscreen and/or off—Tramp, gamine, prisoner, worker, artist, boxer, and Jim Kent will play a real violin.

But more of all that in a future post.

Photography credit: Bamberg Fine Art Photography